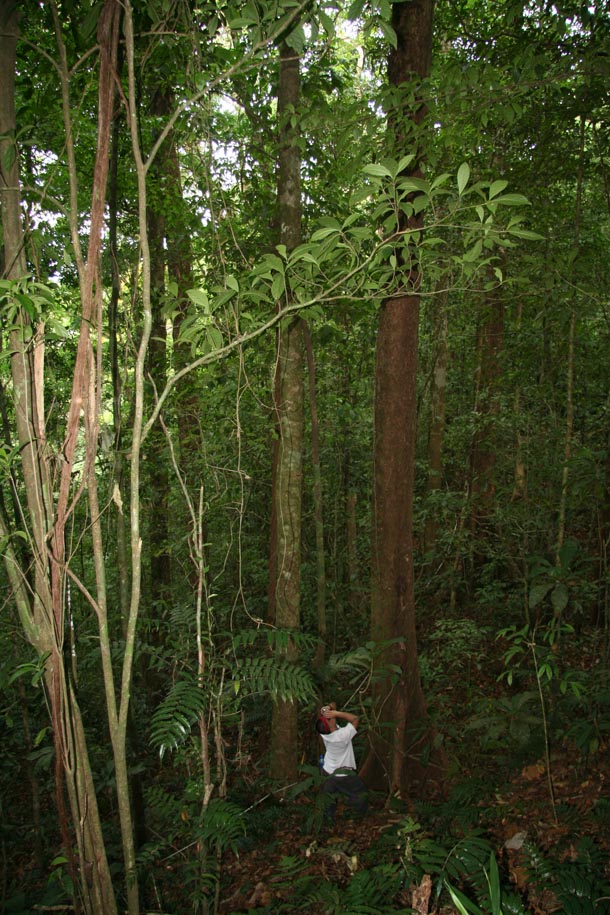

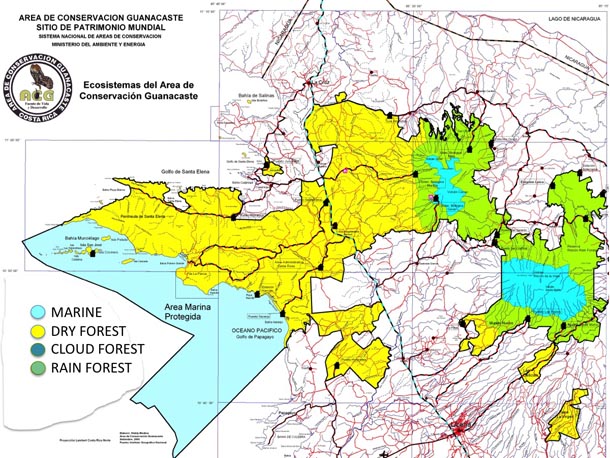

ACG rain forest, green in ACG’s primary ecosystem map, occupies the bulk of the northeastern side of ACG, from about 90 to 1000 m elevation. It goes no lower in elevation because the yet lower northern and eastern terrain is almost entirely intensely farmed agroscape (oranges, pineapple, subsistence farming, palm heart, pasture, etc.). While these lands could be restored over decades (through expansion of ACG) to a semblance of the forest that once grew there 50-150 years ago, such agroscape is way too expensive to purchase today, given the presence of a few other lower-elevation conserved wildlands more to the east in Costa Rica. However, it should be noted that the ACG rain forest on the Caribbean slopes is the last large conserved remnant of the lowland rain forests that once extended from ACG to the Caribbean coast, and therefore is indeed a tiny island with all the attendant problems that come with insularization.

ACG rain forest is more narrowly termed “mid-elevation rain forest” and supports the high level of biodiversity characteristic of tropical intermediate elevation rain forest — which, in Costa Rica, is the most species-rich of all Costa Rican terrestrial ecosystems. In general terms, 2-10 times as many species live and circulate through a hectare of ACG rain forest as through a hectare of ACG dry forest. However, since almost all of ACG dry forest is in some stage of restoration following severe anthropogenic perturbation, it remains to be seen centuries from now how this comparison will eventually play out.

In general terms, ACG intermediate elevation rain forest is largely the product of the moisture-laden trade winds blowing from the Caribbean to the Pacific Ocean and rising when they hit the Cordillera Guanacaste to cool and drop their water as rain, fog and mist. These slopes also receive the full brunt of Caribbean hurricanes moving westward. For a given site, the total annual rainfall ranges between about 2000 and 4000 mm, but this total varies strongly among years at each site. There is a distinct “drier” time of year (January through May), but there always has been enough water falling and frequently enough that most streams and all rivers are ever-flowing, and the soil remains moist, even if the litter dries out somewhat during the lightly emphasized dry season. Many animals and plants in ACG rain forest display strong calendar-defined phenological patterns, though it is not immediately obvious how such synchrony and dormancy-active patterns are cued.

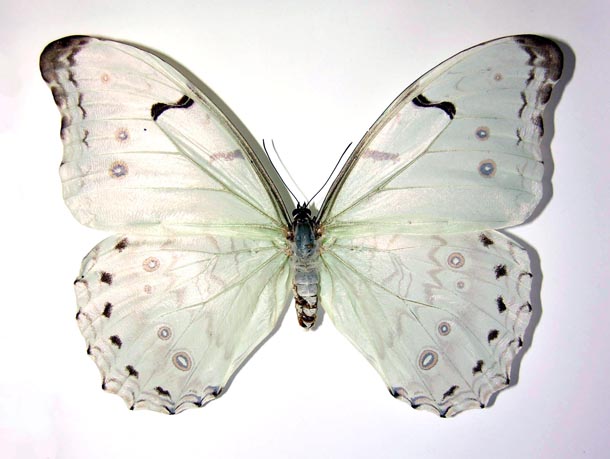

ACG mid-elevation rain forest differs from that of many other rain forest national parks in that the Caribbean slope rain forest wraps around the isolated volcanoes into an interdigitation with Pacific coastal dry forest, as is evident in the ACG ecosystem map. This has two distinctive outcomes for ACG biodiversity. First, in the extensive overlap zones between these two major ecosystems live many species of insects not found deep into either of the zones. A glaring example is the huge white butterfly Morpho catalina (Nymphalidae) that is endemic not only to Cordillera Guanacaste, but also, apparently, endemic to this intergrade zone on the Pacific-facing slopes between about 700 and 1200 m elevation.

Second, distinctive species of both ecosystems can be found growing within a few meters of each other. For example, the big-fruited Manilkara zapota (Sapotaceae) rain forest trees occur side by side with the small-fruited Manilkara chicle dry forest trees in the remnant forest peninsulas on the north slopes of Volcán Orosi. Equally, the introduced dry forest big-fruited Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Fabaceae), or guanacaste tree, occurs side by side with the rain forest small-fruited Enterolobium schomburgkii at Estación Los Almendros in Sector El Hacha. The rain forest large yellow moth Eacles imperialisDHJ01 (Saturniidae) can be collected in the same trap baited with a virgin female as its dry forest look-alike Eacles imperialisDHJ02 at Estación Gongora in Sector Cacao (and they differ by 8% of their DNA barcodes).

A pragmatic scientifically painful outcome of this interdigitation of two major ecosystems is that a specimen cannot be placed ecologically by place names, such as Guanacaste Province (thought of as “dry forest”) and Alajuela Province (thought of as “rain forest”). And (heavily rain-forested) Guanacaste Province even wraps around the north side of Volcán Orosi well into the rain forest of the Caribbean slope.

ACG is fortunate in having been able to acquire the last remaining block of about 2,000 ha of this relatively intact old growth rain forest, the center portion of Sector Rincón Rain Forest (thank you, Wege Foundation and Blue Moon Fund). It is centered on the canyon of the Río Cucaracho, which carries major stream flows off of Volcán Rincón de la Vieja and Volcán Cacao into its confluence with the Río Pizote, and then into Lake Nicaragua.

However, most of ACG rain forest is a fine scale mosaic of old growth rain forest, selectively logged patches (which contributed most of the roads in this zone), and abandoned subsistence farms that operated for only 2-4 decades. Fortunately, the Caribbean slope of ACG was strongly inaccessible, far from centers of populations and political power, and not possessed of a soil/climate interaction that leads to high quality agriculture. Today, all of these perturbed areas are rapidly restoring into variously aged forest, although it will take 100-300 years before it approximates an unbroken rain forest ecosystem. Owing to climate change and insularization (natural boundary on the uphill side, agroscape boundary on the downhill side), whatever form it finally takes will only approximate the original.

At present, it is a fair guess that the ACG rain forest is home to at least 250,000+ species of organisms, though it is unclear what toll insularization by the agroscape will take on these populations; by itself, 30,000-40,000 ha is certainly not large enough to sustain all its original species, and that in turn is broken into various habitats and subecosystems, each represented by only much small areas than those that they once occupied along the entire Caribbean slope of the mountain range extending from Volcán Orosi all the way to Panama. However, GDFCF and ACG are steadily "re-aggregating" small properties through willing-seller negotiations to form a larger block of protected rain forest, one that is now well over 30,000 ha in size and growing incrementally.

ACG rain forest soils, despite being volcanic in origin, are indeed quite “poor” from the viewpoint of farming/ranching, since they are highly leached of their minerals by the year-round rain and moisture at warm temperatures, and because the continual fungal biodegradation of moist and warm leaf litter blocks carbon accumulation in the soil.

While the biological exploration of ACG rainforest has now had two decades of intense inventory of Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies through their caterpillars) and plants, with occasional forays for vertebrates and very specific invertebrates (fungi, spiders, snails), the taxonomic composition of this ecosystem and its millions of interactions remain tierra incognita.

Fig. 10. The single but very, very fragrant flower of Cochleanthes aromatica, an epiphytic orchid 1.5 m above the ground in secondary rain forest at Estación Leiva in Sector Rincón Rain Forest. While the pollinator is unknown, it is very likely to be a night-flying large moth, perhaps in the family Sphingidae. We found the silver-dollar sized flower by searching for the source of the odor filling many square meters of the rain forest understory (24 October 2010).

Fig. 11. Two mountain lions, presumably mother and teenager, captured by a camera trap placed in the forest understory next to Estación Biologica San Gerardo in the ACG’s Sector San Cristobal. How these shy animals, omnipresent throughout ACG, find enough prey in the rain forest to avoid starvation remains a mystery (photo: Ronit Amit 29 October 2005).

Fig. 12. The “flower” of the understory obligatory parasitic plant, Balanophoraceae (perhaps the species Helosis cayennensis?), a plant of ACG old-growth undisturbed rain forest, in this case Bosque PreCafetal on the Pacific mid-elevation slopes of Volcán Santa Maria of Cordillera Guanacaste. This 10 cm tall non-green flowering plant gains all its nutrients from its underground tuberous connection to the roots of its host and no parts of it emerge above the soil until it is ready to flower and fruit (29 August 2012).

Fig. 13. Petrona Ríos, a veteran parataxonomist, wades gingerly through the crystal clear water flowing from the old-growth forested Bosque Precafetal rain forest on the Pacific slope of Volcán Santa Maria in ACG’s Sector Santa Maria. This water has the distinction of being among the 10+ pesticide-free rivers flowing off the Cordillera Guanacaste, free of pesticides because the clouds that condensed in the cloud forest above to create the river had for the most part dropped their pesticide-laden water on the Atlantic side of the mountains as they rose (29 August 2013).

Fig. 14. The bright red cauliflorous fruit of Cojoba costaricensis (Fabaceae) advertises its available fruit in the shady understory of old-growth forested Bosque PreCafetal in ACG’s Sector Santa Maria on the Pacific slopes of Volcán Santa Maria. The bright red fruit has no nutritional value and is not eaten – it is just the flag, indicating the presence of something edible. The real food value is in the black thin aril covering the seeds. When a large bird, such as a toucan or trogon, swallows that seed, its gizzard strips off the aril and the olive-pit-sized seed is then regurgitated (29 August 2012).

Fig. 15. A strange fungus on the forest floor of Bosque Precafetal in ACG’s Sector Santa Maria on the Pacific slopes of Volcán Santa Maria. Its biology is unknown, just like that of thousands of other species of things growing and living in this as-yet unexplored forest (29 August 2012).

Fig. 16. The track of an adult jaguar hind foot in the muddy trail at mid-elevation Bosque Pre-Cafetal in ACG’s Sector Santa Maria on the Pacific slopes of Volcan Santa Maria. Four large toe-prints and one long and large palm print make this track as large as a human hand. This big cat survives by eating just about anything that moves, and some that does not (29 August 2013).