Land acquisition for ACG is a story of the open market.

In the very beginning

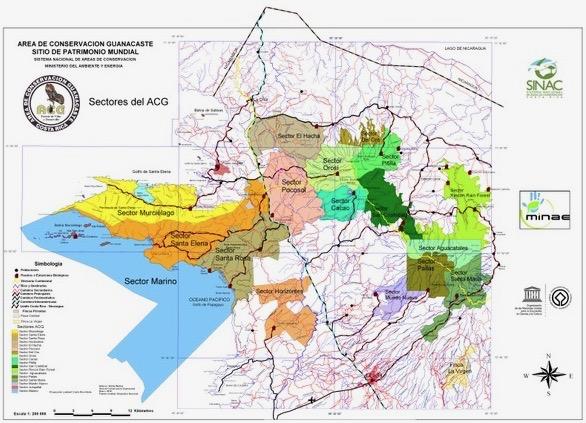

Begun on 1 July 1966, with the decree and expropriation of the Casona and 1,000 hectares of Hacienda Santa Rosa as a National Monument to Costa Rica's early conflicts with U.S. filibuster William Walker in Nicaragua, the first land that was to become ACG was decreed Parque Nacional Santa Rosa (PNSR) on 27 March 1971. PNSR is today Sector Santa Rosa in Figure 2. The 9,904 terrestrial hectares of PNSR, expropriated from the Nicaraguan Somoza family, extended from the Pacific Ocean to the Interamerican Highway, and another 12 miles out to sea to the national limit. Growing from that start to today’s 169,000+ hectares (Fig. 1,2), has been a complex concerted effort by private individuals (both national and international), governments, non-governmental agencies, legislation and national policy. Here we touch on just a few highlights and key policies.

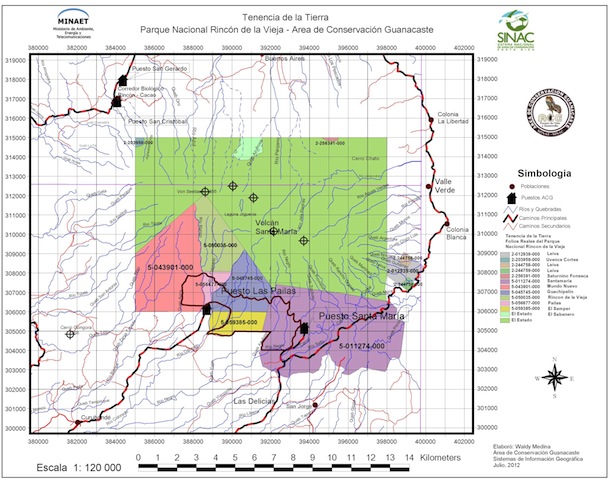

The northern coastline of Sector Murciélago was expropriated from the Somoza family in 1979 and added to Parque Nacional Santa Rosa. The expropriation of Sector Santa Elena began in 1978 and was complete by 2000. In these, and in the only other expropriation in ACG’s history, the government paid what an international court viewed as a reasonable market price. All the rest of the terrestrial ACG was acquired by voluntary negotiated sales or donations. Beginning in 1974, the 11,700 ha Parque Nacional Rincón de la Vieja was decreed a national park, and in 1978 another 2,384 ha were added to it (now known as Sector Pailas, Sector Santa Maria and Sector Aguacateles, see Fig 3). The first willing sale was conducted by Alvaro Ugalde and Spencer Beebe to obtain the yellow rectangle.

In June of 1985, Janzen and Hallwachs wrote a report on the experience of seeking a protocol for non-violent removal of about 1,500 gold miners (Fig. 4) from Parque Nacional Corcovado in southwestern Costa Rica. This produced a set of concepts that came to govern the subsequent expansion, through purchased land acquisition, of the original PNSR into today’s ACG.

In its most brief form, this pragmatic land acquisition was driven by the realization that for a large biodiverse tropical wildland to survive through its acceptance by society:

a) It has to be large (and diverse) enough to sustain the biological needs of hundreds to thousands of ecologically fragile species and do this while being able to tolerate mild footprints, and accidents, by many different kinds of users of its society. To attain this size, the land must be purchased on the open market through normal arm’s-length transactions (climate change problems, for which large size and diverse ecosystems are at least a partial remedy, did not become painfully visible for ACG until about 1990). This meant that land purchase was opportunistic, slow, scattered on the landscape needed, and of variable pricing. It only gradually consolidated ACG into its current highly irregular shape, which is largely due to different histories, rather than biological planning. But this also meant that ACG was not born into a community of disgruntled former landowners.

b) It must provide goods and services to its local and national neighbors, payment that is at least somewhat adequate compensation for ACG presence as a conserved wildland; it must not be a parasite on its society. In the ACG example, this began as 100% local employment for the entire staff (150 at present), intense field-based science and biology education for all neighboring 4th, 5th and 6th grade children, water (once it has flowed out of ACG), intellectually interesting employment, and novel interactions with neighboring commerce. All of this provides a sense of occupation and neighbor ownership, something that a conserved wildland conspicuously lacks, but is widely accepted in Costa Rica and other countries on their way to greater civilization.

c) It has to be based on the concept that “if there are seed sources, tropical forests can and will restore/regenerate themselves”. This in turn means that the purchase process extends to large areas of land and vegetation in all stages of previous destruction and perturbation, and that species and fragments of communities that are in no apparent danger of extinction are valued members of the eventual community in their role as promoters and perpetuators of naturally-occurring restoration processes. When beginning the centuries-long restoration process for tens of thousands of newly acquired hectares, the process must be ongoing naturally, since there is no way that the resources could be available to restore this by human hand, and besides, in many cases there is no model to follow. Four centuries of use have thoroughly erased any semblance of pre-Colombian ecosystems. Nature has to be left to re-find itself with the contemporary actors and their dance floors. While there are many innovative ways to speed restoration (e.g., planting cover crops to eliminate old pasture, using agricultural waste to rejuvenate soils and reroute deflected succession), they all are costly and GDFCF and ACG generally decided to use these funds to purchase more habitat for long term restoration, or for speeding recovery of severely disturbed small critical sites.

Expansion of PNSR to the agroscape, and consolidation into one continuous parcel

The period 1985-2013 may be characterized as “buy every neighboring farm and ranch available, to the degree that donations permitted, and apply any-and-all management actions that would allow the exhausted pastures and low-grade croplands to begin to regenerate their forests, and build a staff of “psychological owners” who specialized in carrying out their specific ACG management specialties. A critical component was stopping the logging and hunting, but most critically of all was putting out the dry season fires set by a multiplicity of causes. The results were spectacular, with young forest rapidly beginning to fill the unburned areas in dry forest (e.g., Fig. 5,6), and doing the same in rain forest if we had the funding to plant a woody cover crop to shade out the grass.

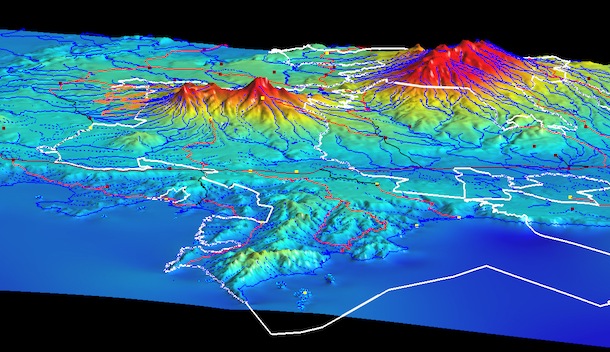

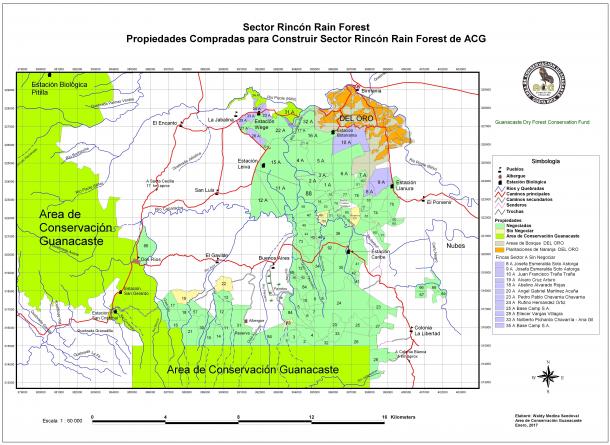

Between 1986 and 2013, a total of 300+ properties were purchased on the open market from a dense mosaic of rural owners in order to fully join the three disparate national parks (Santa Rosa, Rincón, Guanacaste), two wildlife refuges, multiple NGO-owned properties, and newly purchased properties into one solid biophysical unit. The purpose was to have that biophysical unit (Fig. 1, 2) extend from the Pacific Ocean across the lowland dry forest, up over the cloud forest tops of the volcanoes, and down into the Caribbean rain forest (there was never a realistic hope of it extending to the Caribbean shore). The goal was, and still is, that the entire unit would be an unbroken swath of intergrading ecosystems across which species can move with the climate changes that are now in progress. An illustrative case is the purchase of the Sector Rincón Rain Forest complex of former farms on the Caribbean side of the Rincón de la Vieja volcano. This land purchase progression, still underway today, is focused on the most northern portion of Sector Rincón Rain Forest.

In 1998, when we all thought that land purchase for ACG expansion was nearly done, and intense fund-raising for that purpose was winding down so as to more intensively integrate the ACG with Costa Rican society, Oscar Alvarado (Fig. 7) arrived on his motorcycle in the Administration Area of Sector Santa Rosa, to beg that we visit “his” forest on the north side of Rincón de la Vieja. This forest borders the ACG boundary (Sector Aguacatales) and hosts his ecotourism operation “Las Bromelias”. The NGO for ACG, the Guanacaste Dry Forest Conservation Fund (GDFCF) had just been founded in 1997 with the funds from the Kyoto Prize in Basic Science to Daniel Janzen, and the focus at that time was on building programs (including building endowment for future staff job security) rather than on land purchase.

We told Oscar that we had almost no further donations earmarked for land purchase and had let lapse most of our connections to the world of those potential donors. However, Oscar was persistent and convinced us to visit. When we saw "his" forest, a forest that we had not realized was really there, and joined it, in our minds, with the oncoming climate drying that the dry forest side of ACG was obviously experiencing, we realized that we could not let that forest die by logging; which would be its obvious fate if not purchased. As for Oscar, he wanted it all purchased from his neighbors by ACG, so that his ecotourism lodge and land would be surrounded by good and protected forest.

In 1999, Sigifredo Marín (Fig. 8), the former ACG director and then the GDFCF land dealer and field project director, told Oscar to call together all the 20+ very humble landowners (see Fig. 11 as well as the mule owner in Fig. 8) to a meeting in Buenos Aires, the neighboring rural town. We met and explained to them that we did not have funds for total land purchase, but were willing to start in again to raise them, if, and only if, they were all willing to pledge to do nothing to the forest on their lands for a year, and not sell their farms (almost all had already moved out, leaving the area dotted with abandoned houses and overgrown fields). Sadly, in 2000, we met them again and informed them that we had achieved only $100,000 for land purchase. We told them that we could therefore only purchase their properties one by one, as funds were accumulated, rather than in one fell swoop as we had hoped. We released them from their pledge, and the race against the speculators and the loggers began. In the seven years that followed, while GDFCF purchased 55 properties (Fig. 10), we lost two to the loggers (Fig. 9), and two to speculators.

Each individual land parcel purchase by GDFCF is backed up by a title and bill of sale, registration in the national property registry (Catastro Nacional), title checked to be certain that there are no liens on the property (often the seller uses part of the purchase price to pay off earlier loans from the bank, loans collateralized by the land), newly surveyed land map, and property taxes paid in full. Buildings on the property are either converted to field stations or allowed to be carried off piece-by-piece by the neighbors. If there are crops or livestock still on the land, a portion of the negotiated settlement generally allows the last crop to be harvested and/or 6-12 months for cattle grazing before removal (in the dry forest, ACG actually rented pastures to thousands of cattle acting as biotic mowing machines, in order to reduce the fuel load in case of fire, but this is not necessary in the rain forest side of ACG). GDFCF registers the full price of purchase, resulting in hefty annual land tax bills in subsequent years. The overall concept is that the land as a whole unit (e.g., all of Sector Rincón Rain Forest) will eventually be donated to the government and formally registered as “national park” under national park legislation at the time when Costa Rican national park laws have evolved to the point where ACG can fully perform the needed forest management protocols for the Sector, rather than be entangled in the strictures dictated by current national park laws. In the meantime, GDFCF receives several forms of private and governmental Environmental Service Payments (Pagos Servicios Ambientales) that help GDFCF with salary, operations and tax expenses for the land.

Sector Rincón Rain Forest is currently blessed with minimal protection, occupancy and surveillance by 8 parataxonomists working across four remote research stations who also double as Sector Caretakers (Encargado de Sector). For details, please see terrestrial parataxonomy and also the ACG website.