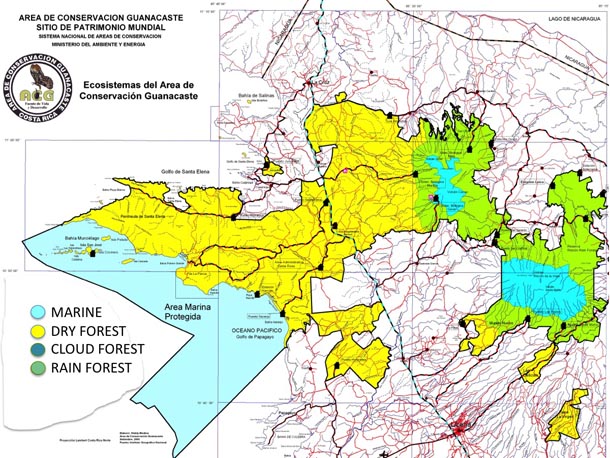

First established as the 23,000-hectare marine portion of the new Parque Nacional Santa Rosa in 1971, the ACG marine ecosystem was initially ignored, other than hoped-for protection of spectacular numbers of Olive Ridley nesting sea turtles (mostly at Playa Nancite) and prohibition of mass commercial fishing or fishing with explosives. Then, in 1987, the marine national park protection status was extended to the northwest along the coast as a six-kilometer wide area of an additional 20,000 hectares, to generate today’s 43,000-hectare Sector Marino, which includes the Islas Murciélago, an archipelago of small islands off the west side of Peninsula Santa Elena. In 2018, the Bahía Santa Elena, which borders ACG, was designated a Marine Management Area. This bay has a completely undeveloped shoreline, rich and abundant mangroves, and serves as a breeding ground for several marine species, including dolphins, whales, and turtles, as well as the endangered whale shark and several species of rays.

While Sector Marino has long been a site of artisanal fishing, which intensified during the Sandinista-Somoza war that drove fishermen south from Nicaragua, the long distance from Cuajiniquil and somewhat treacherous seasonal heavy winds have largely protected it from over-harvesting. Once the political turmoil of the expropriation of Sector Santa Elena was completed in 2000 (see chapter 17, The Green Phoenix), the long and still ongoing process of weaning the artisanal fishing out of the dying coastal fishing industry from its direct marine carnivory in Sector Marino began as an act of marine ecosystem restoration akin to the ongoing and highly successful terrestrial ecosystem restoration that had begun 30 years previously with the declaration of Parque Nacional Santa Rosa, and intensified from 1985 on with the germination of ACG. Sector Marino is to be a 100% no-take Sector of ACG, but an historical lack of funding for adequate enforcement and patrolling means there is continued pressure on fish, lobster, shrimp and other species in the protected area.

While the islands in Sector Marino were almost cleaned of their terrestrial biodiversity due to fires set by camping fishermen, introduced Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus), and at least four centuries of logging (and probably millennia of indigenous hunting and harvest), the underwater biodiversity is still extremely diverse and now recovering. The high contemporary biodiversity is based on reduced artisanal fishing in these distant and wind-prone waters, and second, on the upwelling of deep-ocean mineral-rich waters bathing the geologically diverse rock cliffs, sand and pebble beaches. The major mangrove swamps in Bahía Potrero Grande, fed by the seasonal Río Potrero Grande and the rainy season runoff from many small streams carrying forest litter, also adds to the diversity of habitat types, and hence species, within this ecosystem.

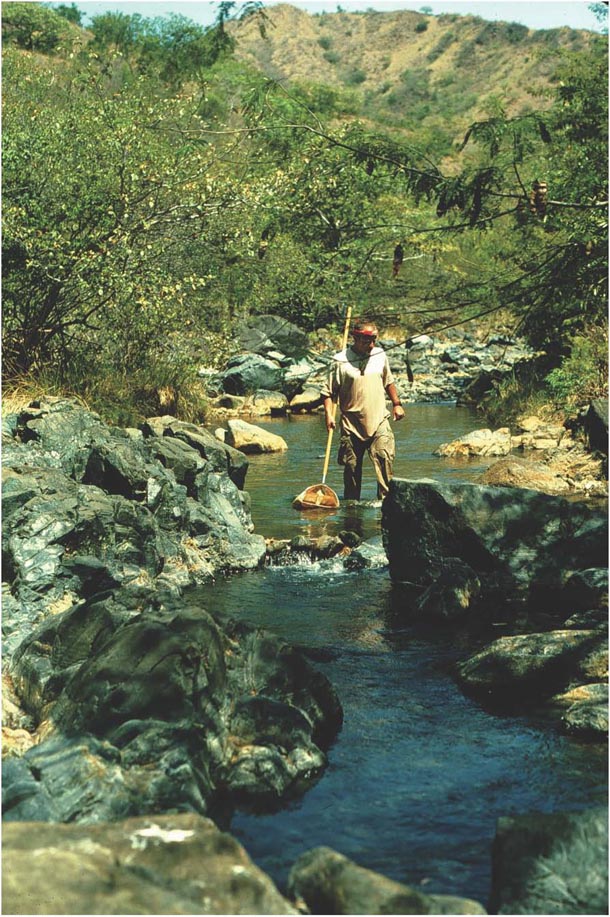

Early on, quick-visit short-term biodiversity surveys of fish, invertebrate and coral species in Sector Marino showed clearly that it was among the most species-rich and habitat-rich areas of the Costa Rican Pacific mainland coast. In 2015, a collaboration between GDFCF, ACG and the Centro de Investigación del Mar y Limnología (CIMAR) at the University of Costa Rica resulted in the initiation of the first systematic marine bioinventory of Sector Marino using DNA barcoding. The ongoing project, dubbed BioMar, has confirmed the biodiversity richness of the ACG marine environment. Since its inception, the inventory has catalogued over 1,100 species, increasing the list of known species from this area by over 885, including 69 species believed to be new and undescribed. The project is led by CIMAR senior scientist Dr. Jorge Cortés Núñez and GDFCF Vice President Dr. Frank Joyce, as well as two parataxonomists who are solely detailed to work in the marine sector.

The combination of marine biodiversity restoration in Sector Marino, along with the BioMar bioinventory project, and continued community investment, as well as educational programs about the protected area have begun to open the door to a nascent ecotourism economy, as opposed to one solely dependent on resource extraction. There is also rising awareness of the insidious marine contamination becoming every day more abundant on Costa Rica’s Pacific coast, but relatively light in Sector Marino because the land side of this sector is not “developed” and will not be, and because of the idiosyncrasy of local currents. The beaches of Sector Santa Elena and the northern part of Sector Santa Rosa appear to be among the only unperturbed beaches without clearing at their edges.

Alongside the bioinventory work, there has also been a concerted effort, beginning in 2018, to invest in research dedicated to learning more about some of the marine-terrestrial migrants of Sector Marino: the sea turtles of ACG. Sector Santa Rosa supports some of the most globally important nesting beaches for Olive Ridley sea turtles. Other species, including the Green, Leatherback, and Kemp's Ridley, are also known to nest on ACG beaches. Our research aims to aid understanding of the dietary and habitat needs of sea turtles, both on land and at sea, in order to protect these vulnerable creatures. The interesting phenomena of ACG jaguars preying on nesting sea turtles has also captured the attention of the sea turtle biologies and they are working to document and better understand this unique predator/prey relationship.

It is generally unappreciated that marine biodiversity is a great deal more than red snapper in the market or pretty aquarium fish. The Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean, and coastal region, easily has as rich a natural history as the adjacent mainland, but the marine world is constantly examined through the lens of edibility, along with recreational sportfishing. Even though most people know what a coral reef looks like, humanity is about as ignorant of marine biodiversity as it is of species from the deep rain forest.